Pendant la Seconde Guerre mondiale, le RDX, un puissant explosif, était fabriqué pour le gouvernement américain à Holston Ordnance Works, sur les sites de Tennessee Eastman. Au plus fort de la production, vers la fin de la guerre, l’usine de munitions produisait un million et demi de livres d’explosifs par jour. De 1943 à mai 1947, Tennessee Eastman était responsable de la gestion du complexe de sécurité nationale Y-12 à Oak Ridge (Tennessee), qui produisait de l’uranium enrichi pour le projet Manhattan.

Tennessee Eastman a été missionné par le Corps des ingénieurs de l’armée américaine pour gérer le site Y-12 durant le projet Manhattan. La société a transféré des scientifiques de Kingsport (Tennessee) sur le site et y a exploité l’usine de 1943 à

Le général Leslie Groves, commandant du projet Manhattan, a reconnu la réussite de TEC dans la production de RDX et a utilisé les ressources de l’entreprise pour l’exploitation de l’usine Y-12 (connue sous le nom de Clinton Engineering Works) à Oak Ridge, dans le Tennessee. Fred Conklin a été nommé directeur de l’usine Y-12, et les scientifiques et ingénieurs d’Eastman ont été transférés de Kingsport à Oak Ridge. Eastman a géré l’usine de janvier 1943 à mai 1947, date à laquelle la société a demandé l’autorisation d’être déchargée de la responsabilité de l’usine Y-12.

The Manhattan Project came to Roch- ester on Christmas Eve, 1942. It Was the second Christmas at war for the United States. The year before, a Japanese sneak attack on Pearl Harbor sent the nation into a second world war a struggle for survival in which the Axis powers of Germany, Japan and Italy still held the upper hand. Nazi Germany had conquered Europe from the English Channel to Stalingrad and from the French Riviera to Norway. Adolf Hitler had just ordered what would become known as the Final Solution the extermination of Europe’s Jews. The Japanese held sway over most of the Pacific and its vital regions that produced oil, tin and rubber, although the tide had begun to turn with a surprise American naval victory at Midway Island in June 1942. It has been called the last good war, the last time when the issue was a cut-and-dried case of good against evil.

There was no other way. It was total war. Total commitment. Nearly every family had a son, brother or husband in uniform. By the end of the war, 42,000 Rochester men 8 percent of the city’s population had joined the armed services.

America was making good on its boast that it was the Arsenal of Democracy. Most industries converted entirely to war production. From tiny machine shops to corporate giants, industry turned out everything from chewing gum for GI field rations to bullets, bombs and airplanes. Rochester’s industries were no exception. Factories were busy three shifts a day, seven days a week.

Overtime was the rule. « I worked in the engineering department, writing instructions on calibrating and testing instruments, » said Lloyd P. Merrill, a Taylor Instrument retiree who worked on the Manhattan Project « The company had a Victory Shift four hours a night, two nights a week, and people like me, who usually didn’t get their hands dirty, went down into the factory at standard base pay to help with the production. » That production didn’t stop for holidays. On Christmas Eve, 1942, James C. White was in his office on State Street He was vice president of Tennessee Eastman Co., a subsidiary of Eastman Kodak Co.

His job was becoming increasingly difficult because Kodak was shifting entirely to war production work not only making film for the armed forces, but turning out high-precision telescopes, cameras, rangefinders, rocket launchers and bridge pontoons. Tennessee Eastman was rushing production of the new high explosive RDX 50 percent more effective than TNT at its Holston Ordnance Works near Kingsport, Term. « White’s phone rang. It was Lt CoL Leslie R. Groves, the Army Corps of Engineers officer in charge of the Manhattan Project Groves was impressed with Tennessee Eastman’s work on RDX.

The government, Groves told White, was beginning a top secret project that would dwarf RDX. Part of the project would be based in a new city to be built in an isolated part of eastern Tennessee. Would Tennessee Eastman be interested in operating a factory for it? « I told him we were already stretched too thin, » White wrote later. « We were running the RDX plant At that time, we only had about 6,500 employees, and of these, 2,200 were on military leave. You can see why we choked a little bit when thinking about taking on this new job. » White passed on the request to Perley S.

Wilcox, Tennessee Eastman’s president He also balked. But just before the new year began, White arranged a here were very I few people who knew what was going on. The workmen down there in the production area would say this was a damn peculiar factory. Carload after carload of material coming in going out. – James C.

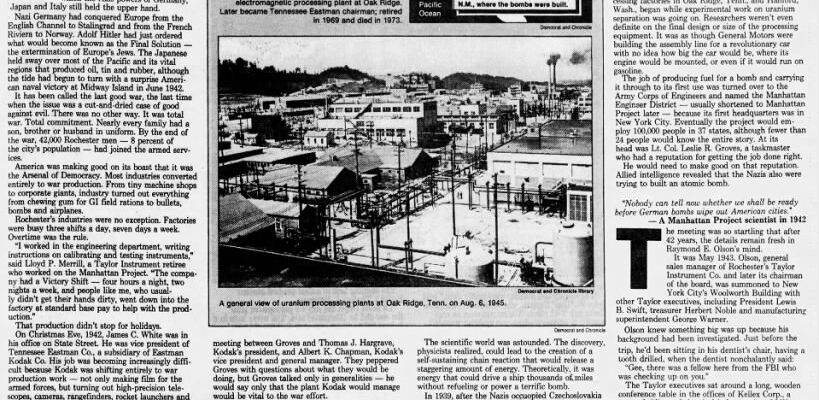

White Vice president of Tennessee Eastman Co., a subsidiary of Eastman Kodak Co., which ran the Y-12 electromagnetic processing plant at Oak Ridge. later became Tennessee Eastman chairman; retired in 1969 and died In 1973. Canada 500 miles J Q raa. ferS& – ‘Cs, « ! i Uni,ed s,ates Aoches,e:?’ t to Alamot, if t- New M.xico , 4 l Oak Rida. J and nothing l TnnM I .

(MMOb Y. Uranium for tha Manhattan Project j Vsk waa procaaaad in Hanford, Waah., . j and at a Tannatao Eastman plant 1 in Oak Ridge, Tonn. The radioactive j products were sent to Loe Alamot, ijEM 1 N.M., where the bombe were built. , »,I » »UI » » « .i…L-i-V.

OamocrM and ChroncK Ownoef M and Chronic! Bbrary A general view of uranium processing plants at Oak Ridge, Tenn. on Aug. 6, 1945. meeting between Groves and Thomas J. Hargrave, Kodak’s president, and Albert K.

Chapman, Kodak’s vice president and general manager. They peppered Groves with questions about what they would be doing, but Groves talked only in generalities he would say only that the plant Kodak would manage would be vital to the war effort. « He (Groves) convinced us there was a real job to do, » White said. « I can remember we tried to bore in on him as best we could. We asked him what the job was.

He would not tell us not until he got us signed up and got everybody cleared. We were blind we didn’t know what the job was. » Kodak agreed to run the factory and soon discov- ered what it was one of two plants in Oak Ridge, Tenn., that would purify uranium to make an atomic bomb. The plant eventually would employ 24,000 people and cost $400 million more than $50 million more than it cost to build the Panama Canal from 1904 to 1914. Only a few years before, the idea of such a bomb would have been dismissed as science fiction. IN THE LATE 1930s, physicists attempted to change the atomic structure of matter by bombarding natural elements, including uranium, with streams of neutrons, uncharged atomic particles.

A breakthrough occurred in 1938, when researchers in Nazi Germany accidentally split the nucleus of an atom of uranium. They called their discovery « atomic fission. » Democrat and Chronicle The scientific world was astounded. The discovery, physicists realized, could lead to the creation of a self-sustaining chain reaction that would release a staggering amount of energy. Theoretically, it was energy that could drive a ship thousands o miles without refueling or power a terrific bomb. In 1939, after the Nazis occuopied Czechoslovakia and halted the export of uranium, two Hungarian-born physicists called on Albert Einstein, the world-renowned physicist who was a refugee from Nazi Germany.

They persuaded him to write to President Franklin D. Roosevelt informing him of the breakthrough in nuclear physics and warning him that the Nazis could be trying to capitalize on it « I made one great mistake in my life, (and that was) when I signed the letter to President Roosevelt, » Einstein, a pacifist, later said. Roosevelt established a committee to look into the possibility of building a weapon from uranium. But it wasn’t until three years later, when the United States had entered World War II, that the bomb-building program picked up full steam. A study committee had determined that extremely powerful bombs could be made from uranium.

Two types of bombs could be made from uranium-235, a rare isotope of natural uranium, and from plutoni-um, a man-made element created by bombarding uranium with neutrons. But such a project seemed impossible. Uranium-235, for instance, was so rare that only one pound of it existed in every 140 pounds of uranium. At the rate that uranium-235 then could be processed, scientists estimated it would take 12 million years to extract one pound. Further research determined that a bomb could be built before the end of the war, but it would require the most immense research and production program in history.

Scientists settled on three ways of processing uranium two for uranium-235 and one for plutonium. One process would separate uranium-235 by electromagnetic separation, in which uranium would be hurled around huge, oval-shaped magnetic « racetracks. » Another uranium-235 process, called gaseous diffusion, would turn uranium into uranium hexafluoride, an extremely corrosive gas, and pass it through miles of filters with microscopic holes. The plutonium process would place uranium into a reactor an atomic pile and let it create a controlled chain reaction that would turn some of the uranium into plutonium. THE CONSTRUCTION OF HUGE, secret processing factories in Oak Ridge, Tenn., and Hanford, Wash., began while experimental work on uranium separation was going on. Researchers weren’t even definite on the final design or size of the processing equipment.

It was as though General Motors were building the assembly line tor a revolutionary car with no idea how big the car would be, where its engine would be mounted, or even if it would run on gasoline. The job of producing fuel for a bomb and carrying it through to its first use was turned over to the Army Corps of Engineers and named the Manhattan Engineer District usually shortened to Manhattan Project later because its first headquarters was in New York City. Eventually the project would employ 100,000 people in 37 states, although fewer than 24 people would know the entire story. At its head was Lt. Col.

Leslie R. Groves, a taskmaster who had a reputation for getting the job done right. He would need to make good on that reputation. Allied intelligence revealed that the Nazis also were trying to built an atomic bomb. ‘Nobody can tell now whether we shall be ready before German bombs wipe out American cities. » A Manhattan Project scientist in 1942 I1 « »‘I he meeting was so startling that after ffmmm AO voarc tho Hotaila remain tVocri in Raymond E.

Olson’s mind. It was May 1943. Olson, general sales manager of Rochester’s Taylor Instrument Co. and later its chairman of the board, was summoned to New York City’s Woolworth Building with other Taylor executives, including President Lewis B. Swift, treasurer Herbert Noble and manufacturing superintendent George Warner.

Olson knew something big was up because his background had been investigated. Just before the trip, he’d been sitting in his dentist’s chair, having a tooth drilled, when the dentist nonchalantly said: « Gee, there was a fellow here from the FBI who was checking up on you. » The Taylor executives sat around a long, wooden conference table in the offices of Kellex Corp., a new subsidiary of chemical industry giant M.W. Kellogg Co. Twenty others, mostly Army officers, lex s Percival « Dbbie Keith, a hard-drivme engineer. ueuueuieu, lie uuu uie i ayiui eiupiuyces, we nr nhniiT.

rn enter inti the mnniitnrtiire nt a n ant. in which will be carried out the world’s largest – i’ .n -‘i ‘ i.i .1 « . eAut:i uueiiL. vv e Ldi l Leu viju wriHi. il is.

iiuL me Germans are working on the same thing and it is a – mra Tf CCA Ttrtlrt T l rt l q h qo tirot IA hatra unno in 1 UVV lV OVV TVikV j. JU-liOllVO tUOln II Wilis 10 rr ri rrr tr cral tho form o rt oi iFPnnHn i – tKm mn » Keith paused to let the words sink in. Kellex, he continued, would build the plant and r i.urii iix iiiiHrHi.if in iivtr ill iiriiiiri I iHriiiiiH. flv I r TncitTiiTnent. umilrl Hp ackpH tn ennnlv lorcro nnonti.

» ties of instruments. The work would take nrinritv over all other war production work Taylor was doing. It would be top-secret work, possibly thank- i tccu. i ney asKea us to iaiK n over in our noiei room and decide by the next day, » Olson remembered..

https://www.newspapers.com/article/democrat-and-chronicle-the-manhattan-pro/77787500/

https://www.newspapers.com/article/democrat-and-chronicle-the-manhattan-pro/77787500/