Deep media

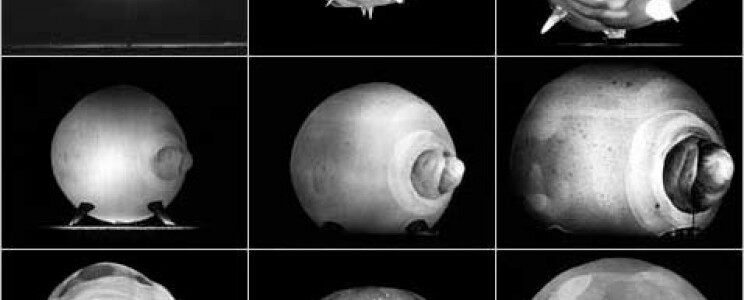

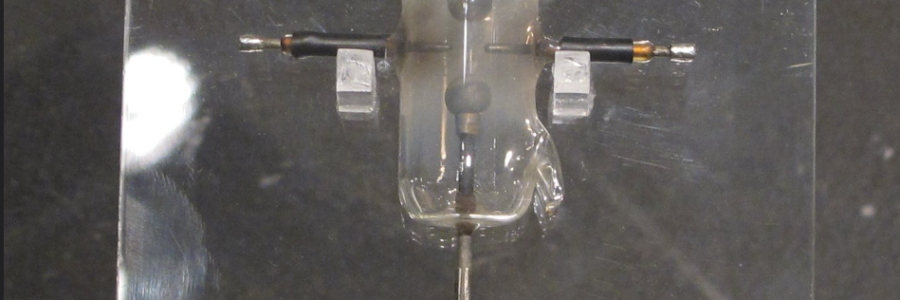

This article considers the pre-history and history of EG&G, Inc., a key contractor in America’s nuclear weapons programme in the Cold War. EG&G was cofounded by M.I.T.’s Harold Edgerton, Kenneth J. Germeshausen, and Herbert E. Grier after World War II in order to serve the nuclear weapons timing and firing needs of the U.S. Department of Defense and Atomic Energy Commission. The three men began their collaboration in the 1930s at M.I.T. with work on flash photography. Indeed, their partnership began in high-speed ‘stroboscopic’ photography in the 1930s, became focused on nuclear weapon timing and firing in 1945–50, and eventually re-focused on high-speed photography in the 1950s. Instead of emphasizing, as others have, the reproduction and circulation of photographic images of nuclear detonations, this article examines how the convergence of photographic and ballistic regimes was constructed around what we call the ‘deep media’ of timing, firing, and exposing.